Today would have been my Nonno’s 90th birthday. He wasn’t a perfect man – none of us are. He was a selfless man and he’s the reason I’m here today. He’s also the reason many Italian migrants to northern suburbs Melbourne found their way in their distant new home.

Post-World War II Italy was not a prosperous place. Particularly in southern Italy, opportunity did not appear to be on the horizon. In much the same manner that I imagine current day asylum seekers make the impossibly tough decision to leave the relative surety of their homeland, my Nonno Michele Pizzichetta made that impossibly tough decision to get on a boat headed for a little-known country on the opposite side of the world. He left a small town, San Severo, in the Puglia region, for a 2-month boat trip. He did this on his own, leaving behind his wife and two very young children (my Mother being one of them). He arrived in Melbourne, Australia on 26 November 1952. Imagine that for a moment – a 25-year-old man, leaving behind his young family, to see if a better life existed in a mystery land so far away it took nearly two months to get there. It’s so difficult to comprehend as it’s so far away from the world in which I find myself in – a world that was made possible by his selfless move in 1952.

In his own words (intentionally left in his broken English), from an interview with the City of Whittlesea in 2001:

“I was in the army and I was look for the go out of Italy because in Italy not many jobs and I want to make some future to my family. Matter of fact I did my ideas come to, I did I come to Australia I like, I been a like it first since I come here. Another thing too I remember very well when I buy this block of land in Thomastown in the Poplar Street, corner Poplar Street and Boronia Street when I buy that I was a feel to be really own something in Australia in Thomastown and then I bring my wife and the children and look forward to build the house, I did build the house through the Building Society and I been paying the bank 1971. I work very hard because I used to work Saturday and Sunday one hour every change they do work and I saved a bit of money to pay the house off. When I pay the house off I went and see my Mother that’s after 18 years I been in Australia I went and seen my Mother because my Father died two years after I been in Australia, the first time I come. After I went seen my Mother I left money for the house I leave my wife money for food and children and went and seen my Mother. I take the time off from the job a bit of a holiday and went and seen my Mother. I stay in Italy the first time nine weeks it is a part of my holiday I been keeping that holiday for a few years they grow. Then when I come back I see everything the right way. I was worried my Mother not was well because was very old. Three years after my Mother died and I was happy I been to see. I been carry on some things you know I come back to Australia and work again and that’s my life I keep a go like that”.

It would be two long years before my Nonna, Mother and Uncle could make the journey to Melbourne to join him. He spent those two years doing whatever work he could to get by, while also buying a block of land with a bungalow in the developing northern suburbs of Melbourne and eventually building a house on it for the family to live in. They arrived on 11 November 1954. He learned enough English to get by from attending night school and from his various jobs – making materials for suits, and utilising the skills he learned in the Italian Army to work in maintenance and the metal trades.

In 1956, he began what would become a lifetime of community action. I am emotional to learn that he even helped raise funds for the construction of the hospital I was born in: “I been really myself live in my own country I was like you know I cared somebody else, some Italian anybody because in my own country I used to do the same you know, help the people how much I cared and that’s what I did here when I be in Australia. In fact, 1956 I was living in Thomastown I been collected some money to build the Preston Hospital, no can do because not enough money, that’s what you call Community Hospital. I been for years you know collecting big money from the trains, Thomastown and also raffle tickets through the Preston Council and sell that ticket in Cup Day and the profit it went to the hospital. I collect a bit of money door to door around Thomastown that time it used to be two shillings”. Sadly, that hospital is no longer there – it’s been turned into apartments. Another hospital was built further north which would become my birthplace’s replacement. My Nonno also played a role in the new Northern Hospital development and was on the Steering Committee that got it built. On this he said: “I be very happy I did that because I feel I believe that’s why you can help people. I been helping people for the pension for anything they come and ask for me. I used to do this sort of thing in my own country and I now a do here. All my difficulty to me the language that why I be doing a lot more than I doing I still feel happy I did and people all around this area respect me and they do the right thing. I never stop, I still do help them when I can”.

For these numerous selfless acts, my Nonno Michele was awarded the Citizen of the Year. But in his typical benevolent way, he said “I not ask, they give it to me. Yes, I did a lot of things. Many time I try to push the Council at Whittlesea to get road built. Because the children used to go on the school in the winter you have no roads to the children not to the school to go along water and mud. I was feeling very sorry for the children, and I did push the Council that time. I not afraid to knock on the door and ask for the benefit to the people, benefit to the area, benefit I see to this area, no discrimination. I like to see that why because this very good area, you see the people come from different countries I seen never been discrimination for long time. I like to see that way because that’s what should be in every area, every place in Australia”. Wise words from a man lacking a formal education but absolutely not lacking compassion. Although these words were spoken in 2001, they could not be more relevant to the society we find ourselves in now, 16 years later.

He was also actively involved in social groups and events. A member of one of the very few Italian/Australian clubs at the time (meeting in Lygon Street, Carlton, which is still the main Italian area of Melbourne). “I was the Treasurer. You see, around this area, I build two pensioner clubs, the Bocci (an Italian lawn bowls game) club. 22 years ago, City of Whittlesea give a piece of land to make the Bocci club they give all the land and the fence around it – it still there. Us build the row for playing Bocci and it built 22 years ago and now I look after the welfare, Italian welfare in Whittlesea, I look after, I am the President. Before that I build Eastern Thomastown Bocci. Before this, I build the others and the Councillors helped me a lot for build all these citizen clubs in Thomastown. They said 12 years ago start Italian Women Groups. Why I started that Women Groups because I see the woman by themselves. They have nowhere to go, nobody to talk to and my idea, I got the Pensioner Club, I got the Bocci Club, now I gonna start something for the woman, that’s what I did. When I started there were five to six women now there be 200-300, maybe more. They have good fun, they play together, the Bingo, have a talk, have a dance. Many times I go there myself and you have a good time, food together, very good. I like it because I see I do something good for them and now there are too many people there and the place where they are not big enough – I tell them I gonna ask Council to build a bigger place for you”.

My Nonno Michele was the one other migrants to the area would go see when they needed help. He was referred to as the “Welfare Italian” and he said “the Council give me one place where I can meet the people with the problem every Friday from 10 o’clock in the morning to 4 o’clock in the afternoon. And they are very good and happy for that and the fact that people come there for ask for help, they come to pass the time too, play cards, or have lunch together, or some bit of music and play Bingo like that for the Italians. No obligation – the only fee for one year $3 for membership and that’s very good because I want to keep as low as possible, because all that come there are pensioners and the ladies and not rich people, that’s a working class people. Sorry I say that, because in this area they are all a working class, because I remember the rich people never come to this area because the rich people go to Toorak or South Yarra, but here all the friends all working, all get on well together”.

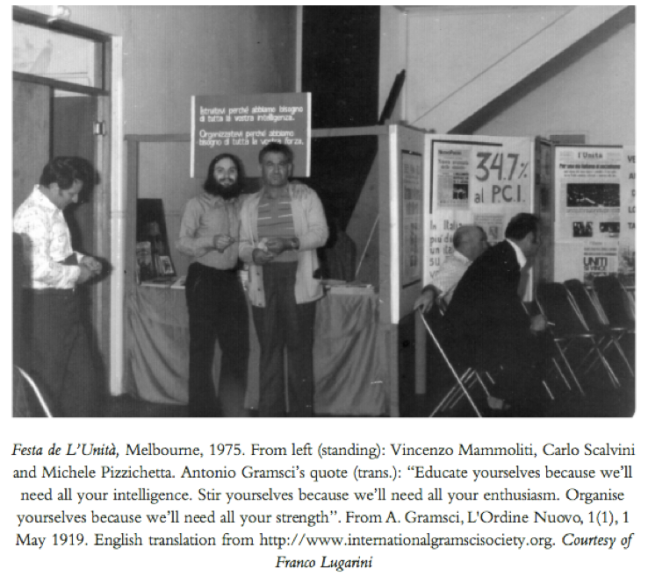

His community action also extended to political activism – he was a member of FILEF, or the Federazione Italiana Lavoratori Emigrati e Famiglie (Italian Federation of Migrant Workers and Their Families), a group that existed from the 1970s in Melbourne. It is said that “not only has FILEF been the launching pad for the professional careers of some of its members, but at a smaller scale it forged the political consciousness of rank-and-file activists and ordinary members who through their activism or presence in FILEF were able to retain, express and foster their political culture, whether communist, Labor or broadly left-wing” (pg xiii, http://www.academia.edu/11331631/Immigrants_turned_Activists_Italians_in_1970s_Melbourne). He is pictured below at some of their meetings (pictures courtesy of the article linked above).

Even my Nonna (Pina Pizzichetta, 2nd from the left below) got involved in the political action, pictured here at a PCI meeting, which was the Partito Comunista Italiano (Italian Communist Party), later renamed the Partito Democratico della Sinistra (Democratic Party of the Left) in 1991 and Democratici di Sinistra (Democrats of the Left) in 1998.

When asked what Italian people hope for, he replied “Italian people not only here but everywhere, they are very good for the family. They look after family and in fact the ladies, the Italian ladies, the grandmother, always look after the grandchildren, they do everything for them, cooking, buy them some suit, shoes or some socks, they grow the grandchildren more than they grow their own children”.

It’s really no wonder that I continue to develop a strong desire to be socially minded and to be actively involved with social programs that assist those less fortunate than myself. I have it in my blood, and I owe it to both of my grandparents who fought for equality and access to basic rights for all, regardless of position or background. They did this with very little wealth of their own, but did it anyway. I’m so incredibly sad that I did not know this story when my grandparents were still here, but maybe I was too young to understand it anyway. So many things I need to say thanks for, but I know that the best way I can say thanks is to continue their legacy. Happy 90th birthday Nonno, I miss you so much (and you too Nonna). I hope I can make you proud one day as I try to contribute to the world around me, much in the way you did.